THE ONTOLOGICAL ARGUMENT

At its simplest, the Ontological Argument claims that, if you understand God to be 'that than which no greater can be conceived', then God must necessarily exist - either because it is greater to exist than not, or because the existence of such a God would be necessary rather than contingent. But more of that in a moment...

Contents

Implications for religious belief

Background

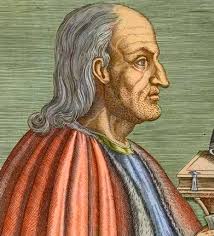

It is commonly pointed out that Mediaeval theologians, such as Anselm of Aquinas, believed in God anyway, so their arguments were not about whether or not God existed, but whether it was possible to show that their belief was reasonable, and thus compatible with the best philosophy of their day. The standard phrase for describing this is: ‘faith seeking understanding’ – that was what Anselm was doing. (See the notes on ‘Faith and Reason’.)

But that did not mean that they were not asking serious questions, or challenging the meaning of religious ideas. They lived at a time when religion was almost universal – but they were not fools; they did not accept the sort of crude ideas of God that are sometimes put about today by fundamentalists or opposed by atheists. The Ontological Argument is a classic example of using logic to disentangle misconceptions about what God means. That’s why it is still relevant, even though we come to the question of God’s existence in a very different cultural and intellectual context. They were not trying to prop up crude beliefs, but were concerned to examine religious ideas in the light of their best available philosophy.

Anselm (1033-1109), was a French monk, from Normandy, who was later to become Archbishop of Canterbury. The 11th century – best known for the Battle of Hastings in 1066 – was a time of war and violence but also of great religious longing. Many of the great Cathedrals in Britain – St Albans, Durham, Salisbury, Chichester, York - were built at that time. The Christian religion was hugely powerful and influential, but could its beliefs be demonstrated by human reason? Anselm was a thinking believer.

Anselm (1033-1109), was a French monk, from Normandy, who was later to become Archbishop of Canterbury. The 11th century – best known for the Battle of Hastings in 1066 – was a time of war and violence but also of great religious longing. Many of the great Cathedrals in Britain – St Albans, Durham, Salisbury, Chichester, York - were built at that time. The Christian religion was hugely powerful and influential, but could its beliefs be demonstrated by human reason? Anselm was a thinking believer.

How this differs from other arguments for the existence of God

The ontological argument is based on a definition of the word 'God'. It claims that, if you understand what ‘God’ means, you understand that he must exist. Notice that this is very different from the Cosmological or Design (or teleological) arguments – the latter depend on looking at the world, and considering whether it provides us evidence for the existence of God. The Ontological argument, by contrast, is based on logic and the definition of what we mean by God. Therefore you can’t use evidence to challenge this argument, instead you can either question its logic, or the definition of God upon which it is based.

Anselm’s first version

Two versions of the argument are set out by Anselm in the opening chapters of his Proslogion.

In the second chapter of Proslogion, the argument is presented in this way:

Now we believe that thou are a being than which none greater can be thought, (aliquid quo nihil maius cogitari possit). Or can it be that there is no such being, since 'the fool hath said in his heart, "There is no God"'? [Psalm 14:1]. But when this same fool hears what I am saying - 'A being than which none greater can be thought' - he understands what he hears, and what he understands is in his understanding, even if he does not understand that it exists… But clearly, ‘that than which a greater cannot be thought’ cannot exist in the understanding alone. For it… [could then] be thought of as existing also in reality, and this is greater.

Therefore, if ‘that than which a greater cannot be thought’ is in the understanding alone, this same thing than which a greater cannot be thought is that than which a greater can be thought. But obviously this is impossible. Without doubt, therefore, there exists, both in the understanding and in reality, something than which a greater cannot be thought.

In other words: something is greater if it exists than if it doesn’t. If God is the greatest thing imaginable, he must exist.

Gaunilo’s objection

The best-known objection to this is from another French monk, Gaunilo of Marmoutier. He argued ‘On behalf of the fool’ that Anselm’s argument could equally be used to show that ‘the perfect island’ exists – on the grounds that one could always imagine more and more perfect islands, and that the perfect island could not be a non-existent one.

In other words: based on the idea that something is greater if it exists than if it doesn’t. Anselm argued that God, the greatest thing imaginable, must exist. Gaunilo’s point is that you can use the same argument to prove the existence of any superlative.

Anselm countered this, by saying that the argument could only apply to God, because anything else was limited, and either did or did not exist, whereas God had to exist. In other words – with an island, you have content specified – palm trees or whatever – you can therefore extend it indefinitely. An island is a limited thing; you can always imagine a better island. But 'that than which a greater cannot be thought’ is unique – it does not specify content at all, only its relationship to everything else – in other words, it is perfection, without giving content to that perfection.

BUT things do not have to exist, just because they are in the mind. The issue is: can ‘the greatest imaginable’ be no more than an idea, or a description of something else?

Anselm had an answer to this in chapter 4 of Proslogion:

For we think of a thing, in one sense, when we think of the word that signifies it, and in another sense, when we understand the very thing itself. Thus in the first sense God can be thought of as non-existent, but in the second sense this is quite impossible. For no one who understands what God is, can think that God does not exist... For God is that than which a greater cannot be thought, and whoever understands this rightly must understand that he exists in a way that he cannot be non-existent even in thought. He, therefore, who understands that God thus exists, cannot think of him as non-existent.

Anselm’s second version

Anselm’s response to Gaunilo is also reflected in a second version of the argument, introduced in chapter 3 of the Proslogion:

Something which cannot be thought of as not existing... is greater than that which can be thought of as not existing. Thus, if that than which a greater cannot be thought can be thought of as not existing, this very thing than which a greater cannot be thought is not that than which a greater cannot be thought. But this is contradictory. So, then, there truly is a being than which a greater cannot be thought - so truly that it cannot even be thought of as not existing.

Most things in the world either are contingent – in other words, their existence depends on factors outside themselves. For example, separated from the environment, your life expectancy is probably about two minutes. You are contingent. But is it possible to have necessary existence – existence that does not depend on anything else?

This is the central question of the Ontological Argument. Either everything that exists is contingent, each arising because of, and depending upon, things other than itself, or, beneath this multiplicity of contingent beings, there is some unchanging, self-existing reality. (See the 'Reflection' in the right hand column.)

Is the argument logical?

Let us look now at some other examples of Anselm’s first kind of argument, which was challenged by Gaunilo:

The tallest person in the room? There will always be one, even if someone taller enters. In other words, the ‘tallest person in the room’ does not specify who that person is – it simply points you to the sort of person that the speaker has in mind. Does the tallest person in the room have to exist? Yes – but only in the sense that the concept exists, and provided that there are people in the room in the first place. That person can be quite adequately be described using other terms, and is only ‘tallest’ by the fact that he or she is in the company of those who are shorter – but we’ll return to that point in a moment.

It is also clear that ordinary, contingent things do not have to exist, just because we can form an idea of them. Let’s take the example of a three humped camel – call him a ‘Humphrey’ for short. I can have a clear conception of a Humphrey – two people could ride on him, but rather uncomfortably! There is nothing illogical in the definition of a Humphrey; but that does not mean the Humphrey exists. So a definition does not imply existence. It simply records a concept. Meaningful concepts simply put together elements of what is already known, and thus describe a complex entity. But that entity may not have separate or independent existence. Either, because there are no known examples of elements being put together in that way (e.g. the Humphrey), or because the definition refers to entities which may be identified by other means. E.g. ‘A level candidates’ do not exist, they are simply ways of describing people. Descriptions may be true, but refer to something that is equally well described in other ways. You may be an a-level candidate, but in another context (e.g. in hospital being treated for some disease) you’re a-level candidacy would not feature – there is nothing in your physical make-up that corresponds to it.

An island only exists because it is surrounded by sea – in other words, it can be defined – and to be defined requires boundaries. The ‘greatest conceivable’ does not have boundaries, and so cannot be defined. It is therefore unique as a concept.

Thus, if we take the word ‘God’ to referring to something within ordinary existence, it is quite possible to deny his existence. I can encounter and understand reality without using that word to describe it.

The theologian Paul Tillich used to speak of God as ‘Being Itself’ – reality itself, life itself, if you like. You can’t say ‘Reality does not exist’; that makes no sense. But you can say ‘God does not exist’ – and by that you mean that you do not find the word ‘God’ a helpful way of describing reality.

In other words – and this is another indication of just how sophisticated mediaeval theologians could be – Anselm is quite prepared to make a distinction between the word ‘God’ and the level of reality to which that word can apply. And once he defines God as ‘That than which no greater can be thought’ – he is really doing no more than indicating the direction in which to look if you want to understand how he is using that term.

He suggests that the term ‘God’ is used for indicating the ultimate, or the perfect, or the absolute, or reality itself. In terms of modern cosmology, you get an ‘event horizon’ as you approach a black hole – the point at which the gravitational pull of the black hole prevents photons from leaving, and therefore the point beyond which one cannot see. Well, one could say that Anselm uses the word ‘God’ to describe the ‘event horizon’ beyond which thought and concepts cannot go. The ultimate.

What he’s saying here, therefore, is that the word ‘God’ signifies the ultimate or absolute. And if you understand the word ‘God’ that way, it makes no sense to say that ‘God’ does not exist. But of course, that is quite different from saying that there is something within the world of contingent beings called ‘God’; something which might or might not exist.

Descartes' version

Another version of the Ontological Argument was given by Descartes. He argued that existence is a necessary part of the meaning of God, just as three angles are a necessary part of the meaning of a triangle. You can’t have a triangle without its three angles, and you can’t have God without his existence. The implication of this is that, once you define what you mean by God, that definition is of something that has necessary rather than contingent existence. But that does not imply that we can prove that things exist just by thinking about them.

Another version of the Ontological Argument was given by Descartes. He argued that existence is a necessary part of the meaning of God, just as three angles are a necessary part of the meaning of a triangle. You can’t have a triangle without its three angles, and you can’t have God without his existence. The implication of this is that, once you define what you mean by God, that definition is of something that has necessary rather than contingent existence. But that does not imply that we can prove that things exist just by thinking about them.

He argues this in Meditation 5, seeing existence as a perfection, and therefore that God – a supremely perfect being – must have all the perfections, including existence. But he is not suggesting that our thought can determine what exists:

… thought does not impose any necessity on things; and just as I may imagine a winged horse even though no horse has wings, so I may be able to attach existence to God even though no God exists.

But there is a sophism concealed here. From the fact that I cannot think of a mountain without a valley, it does not follow that a mountain and valley exist anywhere, but simply that a mountain and a valley, whether they exist or not, are mutually inseparable. But from the fact that I cannot think of God except as existing, it follows that existence is inseparable from God, and hence that he really exists.

[Translation from The Philosophical Writings of Descartes, CUP, 1984]

Kant’s critique

This form of the argument was countered by Kant (in his Critique of Pure Reason) in this way:

- If you have a triangle

- Then it must have three angles (i.e. to avoid contradiction)

- But if you do not have the triangle, you do not have its three angles either.

Therefore:

- If you believe in God, it is logical to think that his existence is necessary.

- But you do not have to accept the idea of God.

Kant argued that existence is not a predicate. In other words, you add nothing to that description or something by saying that it exists.

Points to consider:

Do you agree with the logic of Kant’s argument here?

What does it mean to say that existence is not a predicate?

Now to appreciate Kant’s refutation of this, you have to be aware of a distinction between two kinds of statement:

- Analytic statements are true by definition;

- Synthetic statements can only be proved true or false with reference to experience.

Statements about existence are generally synthetic; definitions are analytic. Descartes is trying to turn an analytic statement into a synthetic statement.

Normally there are two separate things to be linked – the concept and the external thing to which that concept refers. ‘This is what I mean, and there it is.’ But that cannot work in terms of God – because there is no external ‘thing’ to which you can point. And ‘existence’ is normally taken to mean ‘there is an example of’. Hence it makes no sense to say that existence can be a predicate, or part of a definition.

It is worth recalling Bertrand Russell’s way of expanding on the word ‘exists’. In an example (given by John Hick – in Philosophy of Religion) ‘Cows exist’ means “There are x’s such that ‘x is a cow’ is true.” In other words, to say that something exists is not to add to its definition, simply to point out that there are things to which the definition applies.

Monologion and perfection

So what did Anselm understand by speaking of God as 'that than which none greater can be thought'? In Monologion, he spoke of degrees of goodness and perfection, arguing that there must be something that constitutes perfect goodness (God), which causes goodness in all else. (This is like Plato's idea of Forms; Anselm's ‘God’ comes close to Plato's ‘Form of the Good’.)

If you have no idea of perfection, how can you judge between what is good and what is better?

- 'the perfect ...' is in a different category from individual good things;

- 'the perfect ...' is not simply the top of a series of individual things.

God, for Anselm, is not an object, and therefore does not 'exist' in the way in which other objects exist – if he had believed that, Gaunilo’s criticism about ‘the perfect island’ would have been valid. Anselm's idea of God springs from his awareness of degrees of goodness in the world.

In other words, what the Ontological argument is saying in effect is that the mind goes beyond a concern for ordinary, limited things, and is constantly striving to find a perfection that lies on the boundary, beyond which our thought cannot take up. It is about a mental striving, not about what can be defined and known.

Anselm is saying, in effect ‘If you want to know what I mean when I use the word ‘God’, you must appreciate that it refers to that than which no greater can be conceived, the very limit of what we can know and the ultimate in what we can value. It is not something that can be limited in any way, for the mind can always go beyond limited things and look for something greater…’

Modern versions

The most commonly cited modern approach to the Ontological Argument is that produced in Philosophical Review, January, 1960 by Norman Malcolm.

The most commonly cited modern approach to the Ontological Argument is that produced in Philosophical Review, January, 1960 by Norman Malcolm.

Here is the relevant section from my An Introduction to Philosophy and Ethics (p28):

His argument is that God’s existence cannot be contingent (he cannot be the sort of being that might exist or not), since there is nothing that could cause him to cease existing if he does exist, nor cause him to start existing if he does not. Either of those last options would detract from the definition of God as either ‘a being than which a greater cannot be thought (Anselm) or the most perfect being (Descartes). Therefore God’s existence is either necessary or impossible.

But, Malcolm then argues that God’s existence cannot be impossible (for if it were, then ‘God exists’ would be self-contradictory), therefore it must be necessary – in other words, God necessarily exists.

To appreciate the strengths and weaknesses of this argument, it is important to distinguish between logical necessity and factual necessity:

- If ‘God exists’ is logically necessity, then ‘God does not exist’ would be self-contradictory.

- If ‘God exists’ is factually necessary, it is not possible for there to be no God.

Malcolm’s comment depends on this distinction. If the argument were about logical necessity, then he has a valid point; but most people consider the argument to be about factual necessity. But this is not completely new. Kant’s criticism of the Ontological argument also made this distinction: the necessity of a triangle having three angles is a logical necessity, but it is not factually necessary for there to be a triangle at all.

Of course, one could argue that this had been adequately covered already by Anselm himself in the second version of his argument (Proslogion chapter 4).

The other modern development is that from Alvin Plantinga, who used a philosophical technique called ‘modal logic’ to argue that, for a being to have what he terms ‘maximal greatness’ (Anselm had a slightly longer phrase for that, but never mind) it must have ‘maximal excellence’ in all possible worlds – and this is a matter of logic, not astronomy! It means that, whatever state of affairs there might be, however the world might turn out, that being would still have ‘maximal excellence.’ I have to confess that, although couched in language that is perhaps better suited to modern philosophy than that used by Anselm, I really do not see that Plantinga has taken the argument forward by very much. It simply places ‘that than which no greater can be conceived’ in the context of modal logic, and comes out with a conclusion not unlike Anselm’s. (There is more on this on pages 29 and 30 of An Introduction to Philosophy and Ethics.)

The other modern development is that from Alvin Plantinga, who used a philosophical technique called ‘modal logic’ to argue that, for a being to have what he terms ‘maximal greatness’ (Anselm had a slightly longer phrase for that, but never mind) it must have ‘maximal excellence’ in all possible worlds – and this is a matter of logic, not astronomy! It means that, whatever state of affairs there might be, however the world might turn out, that being would still have ‘maximal excellence.’ I have to confess that, although couched in language that is perhaps better suited to modern philosophy than that used by Anselm, I really do not see that Plantinga has taken the argument forward by very much. It simply places ‘that than which no greater can be conceived’ in the context of modal logic, and comes out with a conclusion not unlike Anselm’s. (There is more on this on pages 29 and 30 of An Introduction to Philosophy and Ethics.)

To sum up:

- If we simply think of the ontological argument in terms of the claim that ‘existence is a predicate’, then Kant was probably right, and Descartes and Anselm wrong - for to say that something 'exists' is quite different from saying anything else about it.

- Anselm’s argument shows that some idea of ‘that than which no greater can be thought’ is a necessary part of the way we think, since, every time we ascribe value to something, we do so on the basis of an intuition of that which has supreme value.

- The ontological argument is about how we relate ordinary, conditioned existence to the idea of the perfect, the absolute and the unconditioned.

What implications does this have for belief?

If someone already believes that God is ‘that than which no greater can be conceived’, then Anselm shows that God must exist – for it would be illogical to deny the existence of ‘that than which no greater can be conceived’. Hence, such belief is not irrational, and it is therefore a useful support for the believer. It does not prove that he or she is right to believe that there actually exist something that corresponds to the idea of God, but at least points to the rational basis for such a belief. It is not unreasonable to believe that there is something ‘than which no greater can be thought.’

But what of the person who does not believe already? Is the argument persuasive?

Perfection can remain an ideal; it does not have to be linked to something that ‘exists’ in any ordinary sense of the word. To try to claim that God exists, just because it is possible to link him to a definition whose denial appears to be self-contradictory (i.e. to say that ‘the greatest thing imaginable’ does not exist, is to deny that it is ‘the greatest thing imaginable’) is clever, but pointless. It is no more than a game with words.

In a sense, the philosopher should sit on the fence between believer and unbeliever. The unbeliever is totally justified in rejecting the argument, if ‘God’ is taken to be a being about which a discussion of its existence or non-existence is meaningful. In other words, if God is a being who might or might not exist, then this argument is bogus, because it deals with what we can conceive, not with what is actually there. On the other had, the philosopher will want to point out that the believer need not have a naïve or literal idea of God, and that the Ontological argument performs the important function of keeping the idea of God open, at a level where he is not confused with any finite thing in the universe.

Final comment...

Whether in literature, art, architecture, athletics, politics, music and all other creative activities, we naturally strive to go beyond the practical possibilities that we see around us. The human mind is restless and driven by ideals. It tries to grasp perfection, even if that perfection can never be realised. Religion, in its many forms, along with much of the best secular philosophy, is an expression of that striving. Take it away and we become little more than consumers, grazing animals, drones. ‘That than which no greater can be conceived’ puts the rest of what we conceive into a new perspective.

Perhaps that view is best summed up by Iris Murdoch in her book Metaphysics as a Guide to Morals. She claimed that the argument about necessary existence should be taken in the context of the Platonic view of degrees of reality, and that the ontological argument is not simply a piece of logic, but something that points to a spiritual reality that transcends any limited idea of God. It is also something that goes beyond individual religions:

An ultimate religious ‘belief’ must be that even if all ‘religions’ were to blow away like mist, the necessity of virtue and the reality of the good would remain. This is what the Ontological Proof tries to ‘prove’ in terms of a unique formulation. (op cit p427)

© Mel Thompson