Of hair loss and neural pathways…

This is a very selective autobiography, concerning only three aspects of my life, one of which may possibly be of interests to readers of this website - or not, of course.

I was a great disappointment to my mother. Heavily pregnant nine months after the 5th Essex Regiment arrived home from the war, she was convinced that I would be a gir, and decided to call me Felicity Elaine. Sadly (for her) I appeared with a willie, so she took her revenge by calling me Melvyn and allowing my curly, ginger hair to grow unchecked.

Twenty years later, I was shorn, but assumed that a white jacket and cravat would be appropriate for my first foreign trip – here snapped on the snowfield below the Jungfraujoch in the Bernese Oberland in Switzerland, still one of my favourite parts of the world.

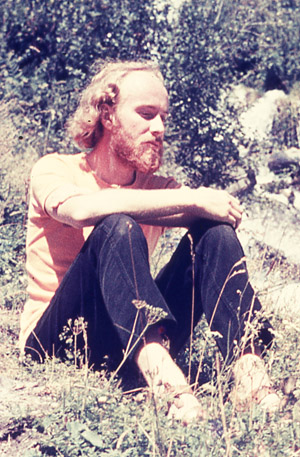

Within a few years, student life at the end of the sixties had turned me into more of a hairy philosopher, or mystic, or poet even. Here I sit by a mountain stream contemplating the meaning of life!

Alas, the hairline receded, leaving me with a monastic tonsure; at which point I decided to take matters of my head into my own hands and shave the dome. By that time, of course, my ginger had turned to grey and then white.

So there you have it; my life in follicle perspective!

But while my hair has gone from the luxuriantly tousled to the relatively smooth, by brain has inevitably and remorselessly moved in the opposite direction, with the gradual etching of neural pathways – the traces of the experiences, events and ideas that have come to direct my habitual patterns of thought and behaviour and hence to explain the contents of this website.

First the easy bit… my photography

I was brought up deep in the Essex countryside, and spent my early days wandering the woods and river in my home village of Little Baddow, so I’ve always felt most ‘at home’ when walking in the countryside and – from an early age, encouraged by my father – to do so with a camera.

This image of swans on the Chelmer near Ulting, Essex, was taken when I was 13 and developed and printed in a little cupboard that served as our home darkroom.

I still love landscape photography. To date, my most downloaded photograph on Shutterstock is this image of the Lauterbrunnen Valley in the Swiss Alps.

Now the more tricky bit… religion and philosophy

My intellectual life has been shaped by the difficult, sometimes painful, juxtaposition of religion and philosophy.

I was brought up as an Anglican, sang in the church choir and became an altar boy. The building, music and ritual coalesced around a general sense that here was something both beautiful and real, reinforced by a mystical sense of universal acceptance that I found as a child in the countryside. It spoke of a reality that I knew first hand; a depth to experience and a sense of wonder that I have never doubted. Yet I found it very difficult, even then as an early teenager going for Confirmation, to square that certainty of experience with the creeds and teachings of the Church. With hindsight, I recognise that my problem was with the whole idea of the supernatural – an uncertain, problematic world in which some believed and others did not, a world utterly different from the natural world into whose depths I was happy to immerse myself. I sensed then that the only real distinction was between the deep and the superficial, rather than the believing and the non-believing;

At the age of 17, I read the newly-published Honest to God, and immediately identified with John Robinson’s argument – our image of God had to go, and with it the whole supernatural realm; exactly what I felt I already knew. I decided to study Theology and applied to King’s College, London, but before going to college, I read Bertrand Russell’s History of Western Philosophy. An entirely new world opened for me; a world in which I could examine and challenge every argument, one in which I could try to achieve intellectual honesty.

To cut a long and rather painful story short, I became an Anglican clergyman, and soon an extremely unhappy one. I found myself on the ‘wrong’ side of almost every argument, desperately trying to understand how it was that people could believe the things that the Creeds taught. On the one hand, I could not be honest about my own beliefs without threatening those that the people to whom I ministered seemed to find helpful; on the other, my integrity was eroded by every attempt to compromise with the unbelievable in the effort to reform the Church. I was an unbelieving clergyman, but married to a believer and the product of a believing family. Yet I remained convinced that the depths of life to which religion, morality, aesthetics and mysticism pointed were of supreme importance. I retreated into the academic world, philosophy and publishing – opting for integrity, but losing the depth and intuitiveness of religion.

Some years later, I found myself drawn towards Buddhist practice, finding there an open-minded exploration of the reality of being human, and a wonderful vehicle for spiritual development without the impediment of supernatural beliefs. My association with that particular Buddhist group did not last, but it provided a useful training in meditation and insights I still value.

Once established on the tabula rasa of the young brain, neural pathways are reinforced by use as each new experience overlays those already set down. Our brain grows with us, as do our thoughts, but the most fundamental pathways are the earliest, and I can still sit alone on a riverbank and sense my earlier self, shedding for a moment the clutter of decades and the regrets about habitual unwisdom and hurts exchanged.

Of course, the most important features of life are neither included in a follicle count nor explained in terms of the intellectual pathways that shape the development of our thinking – but they concern other people, and are not relevant to an appreciation of where I am coming from in terms of the books on religion, philosophy and ethics, or my landscape photography. Hence, I spare you the details; and spare those closest to me the indignity of being included here.

Over 40 years of writing, and almost as many involved with education in one form or another, my early sense of mystical wonder and my dislike of supernatural speculations have given impetus both to my early academic research and to my many publications.