From the Introduction...

After they died, I discovered a strange coincidence. Among those who survived the carnage of the Great War, two of the 20th century’s greatest religious thinkers had faced one another across exactly the same stretch of the Front on the devastated hillsides to the west of Verdun in June 1916. Both went on to describe their war service as the most formative experience of their lives and, out of that hell of exploding mud and body-parts, they were to forge radical new ideas about the role of religion and the future of humanity.

After they died, I discovered a strange coincidence. Among those who survived the carnage of the Great War, two of the 20th century’s greatest religious thinkers had faced one another across exactly the same stretch of the Front on the devastated hillsides to the west of Verdun in June 1916. Both went on to describe their war service as the most formative experience of their lives and, out of that hell of exploding mud and body-parts, they were to forge radical new ideas about the role of religion and the future of humanity.

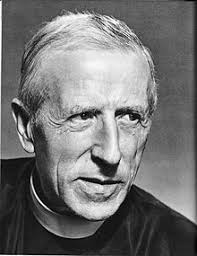

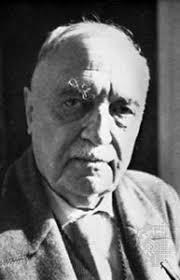

They could not have been more different: one was a Lutheran pastor and philosopher, proud to be Prussian and brought up to be politically and religiously conservative; the other a French Jesuit, fascinated by science and evolution and soaked in traditional Catholicism. Separated by no more than a few hundred yards of mud and barbed wire, they struggled, each in his own way, to make sense of their faith in the face of the horrors they witnessed on the battlefield. Paul Tillich served as a Lutheran chaplain, often also as a gravedigger, Pierre Teilhard de Chardin as a stretcher-bearer. Their subsequent writings do not simply illustrate their own personal struggles with faith and their courage in the face of opposition, but shed light on some of the ways in which our thinking has changed over the last hundred years.

Click here to buy from Amazon in the UK (#ad)

or here from Amazon.com (#ad)

One of the themes of this book – how religion tries to make sense of the experience of suffering – has been dealt with many times before, but the approach I want to take here is very different. Beyond any logical answers given by believers and theologians to the ‘problem of evil’ or their rational refutations by enlightened sceptics, what I am searching for here is a way of thinking and feeling that can help us cope with the facts of human fragility that threaten each of us, whether or not we follow a religious tradition. Insight of that sort comes at a price; both men went through hell, during the war and after it. Paul Tillich had two nervous breakdowns during his war service and emerged with his social, political and religious outlook transformed. Teilhard de Chardin appeared to emerge religiously unscathed, but an examination of his letters and journals reveals that he suffered from severe anxiety states. He felt himself paralysed, unable to act effectively, unless he could see some definite and guaranteed goal to which his action could contribute. For him, affirming and re-affirming his beliefs became his therapy, his way of overcoming the threats he faced day by day on the battlefield and in the years that followed. He judged that, without purpose and direction, we are lost. Teilhard fought against doubt, while Tillich embraced it.

Of course, one might argue that the field of battle is the one place where there is no room for doubt. Orders are given and obeyed; men are trained out of any habits of independent action. On a superficial level, freedom and choice give way to brutal necessity, but that does not preclude a deeper longing to make sense of life in an environment where the chance falling of a shell brings sudden death or slow burial. The front line is all about movement and purpose, attempting to gain ground or being forced to relinquish it. But is that enough to confer meaning? Is a forward charge, in any sphere of life, sufficient to give personal satisfaction? Nietzsche might have found his source of happiness in a straight line and a goal, but is that requirement universal?

So, as we prepare to scan the battlefield, here are some of the questions we might ask: Is it possible to be truly content while living with uncertainty and vulnerability, whether on the battlefield or in a cancer ward? How do we make sense of a world in which death is the only certainty? How is it possible to maintain a sense of yourself, when all that is familiar crumbles about you? Is it possible to find a narrative that makes sense of the world, or is our desire to do so just another proof that life is inherently absurd? Is it reasonable to believe in a God, or Providence, or to trust that, through reason and science, life will tend to improve in the long term? Is war a natural and inevitable part of human life, or a hideous distortion of a potential that is both reasonable and collaborative? And is it sensible to give yourself to a cause, national, global or religious, in the hope that your life will thereby take on meaning, significance and value, or is enlightened self-interest the only reasonable option?

These are universal and perennial questions, and I cannot pretend even to start to offer answers to them. But sometimes such questions are presented to us in a particularly stark form, as I believe is the case in the story of Teilhard and Tillich and their responses to the Great War. ...

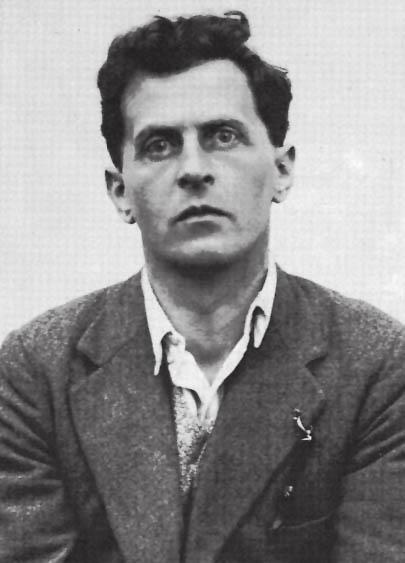

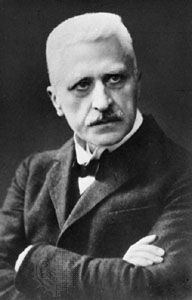

Of course, Tillich and Teilhard were not the only ones to ponder matters philosophical under fire. The French philosopher Emile Chartier was working on the first draft of his book Mars, or the Truth about War, during the battles of 1916 and, on the Eastern front, Ludwig Wittgenstein, having opted for the most lonely and potentially suicidal of posts, guiding artillery from a dugout in no-man’s-land, started noting down ‘The world is all that is the case’ for his seminal work Tractatus. While back on the Western front, a frustrated young artist by the name of Adolf Hitler was reading Schopenhauer, brooding on the perceived injustices wrought upon his fatherland, and hoping one day to become a philosopher and a great leader. They too will have a part to play in this story.

Individually, Tillich and Teilhard fascinated me; together they beguiled me. This book attempts to pay them critical homage. So let us try to enter imaginatively into their thinking as they joined the millions of others who marched into the madness and horror of The Great War.